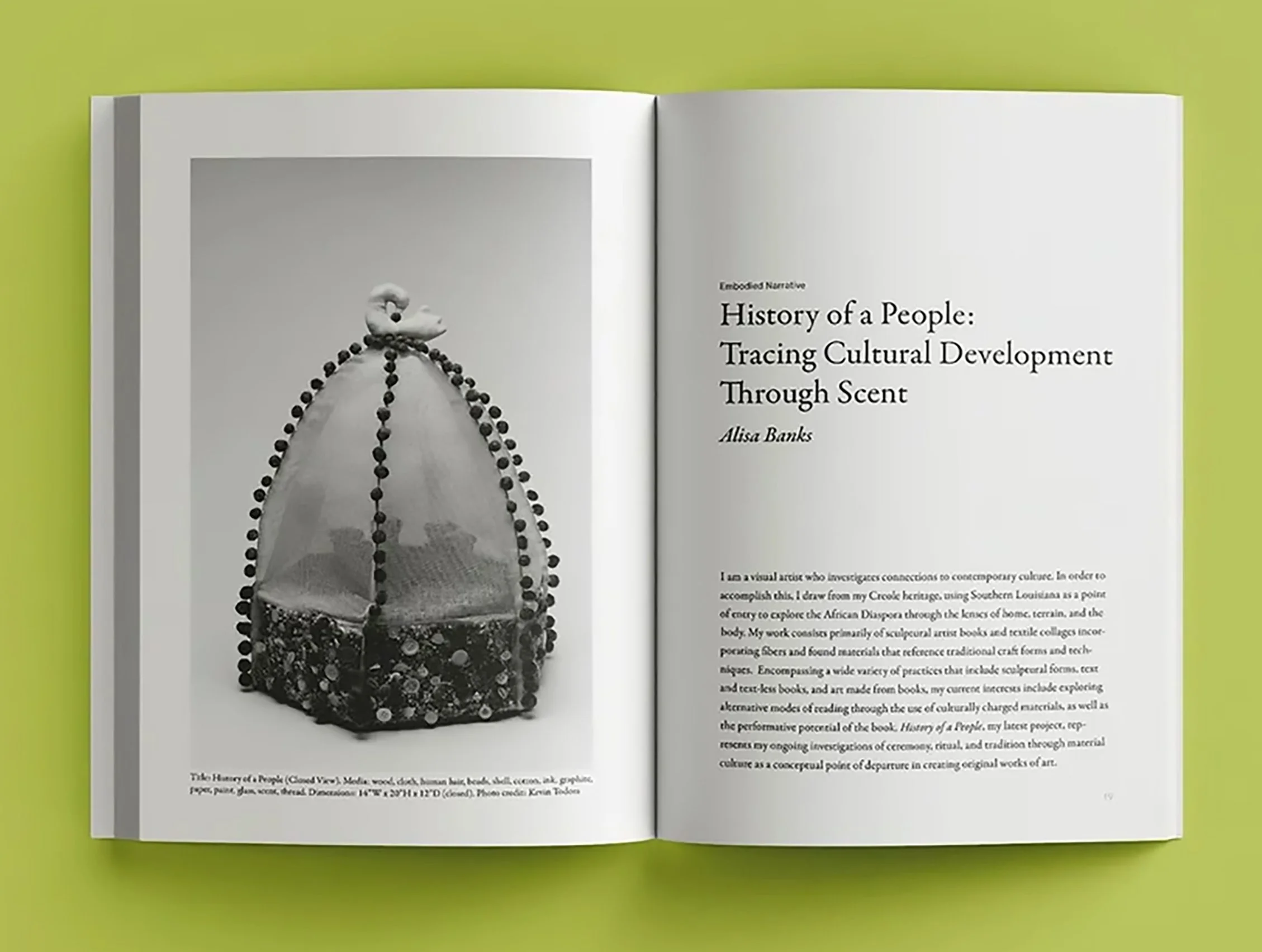

writings

Political Bodies: Agency and Intention

Reading Roots

when is now

When Is Now questions the appropriate time to expect equal footing and humane action for marginalized populations. The basis of the text was conceived during a time of personal upheaval that coincided with the 2016 US presidential election and speaks to feelings of shock, denial, immobility, anger, helplessness, and sorrow concerning the ensuing political and cultural shift in this country and beyond. It speaks to my connectedness as an “unheard” to others who are “unheard” and is a protest against racially motivated acts of terror, unequal citizenship, callous action, and invisibility.

What action to take and when to take it is a personal decision and a multi-faceted community has room for many forms of activism. In simple terms, one form is that of patient activism. Improvements progress slowly and peacefully by living as a “model” citizen by constantly striving for excellence in every aspect of living in order to break down stereotypes. Other methods include engagement in protest by marching, petitioning, and use of the court system, and community volunteerism and stewardship. Yet another form of activism uses physical means such as marching and taking armed and/or unarmed defensive measures.

Activism has facilitated change but at times the gains made toward equal citizenship appear to slide backwards. The call for patience, to wait “for things to get better” is a familiar refrain. Many who reap benefits from past activism manage the daily stress of living with or compartmentalizing feelings of frustration, disbelief, anger, and hopelessness with each report of violence and blatant unfairness against marginalized persons. When is enough, enough? “When is Now?” or “When is Now!”

Click the below to hear Alisa read “When is Now”

apolitical

For several years, we (husband, daughter, and I) spent Thanksgiving Day with a friend - a transplanted New Yorker - her family and friends. Discussions of the latest happenings in music, politics, and culture were the usual accompaniments to the day’s feast. On one occasion, after my friend presented impassioned instructions for activism, I became overwhelmed and responded, “Well, I’m not political.” Time slowed as that last “l” lingered before it escaped my lips. My eyes widened. I immediately realized my error.

Fast forward. My mother's death coincided with the outcome of the contentious US presidential election of 2016, both unexpected events. It was a time of grieving, bewilderment, and confusion. I mourned my mother's death along with what appeared to be the beginning of an era of increased incivility. Not that previous years have been without incident. Reports of violence against "others" in general and Black males in particular, had been escalating. Add that, so many more instances of violence were not being spoken of, such as police violence against black females - a subject that continues to elude news reports. News of the election outcome was accompanied by increasing reports of xenophobic and racially motivated acts of hatred initiated by those who believed the election result confirmed their right to act in this manner. These events sent my mind back and back to a time when intolerance ruled, and though never presented as such, terrorist acts against certain individuals were offensive to a few, were more often seen as unfortunate, and deemed by many to be acceptable.

Reports of violent incidents in addition to extensive house repairs, which were also unexpected, issued in a creative paralysis that I'd never experienced. Thoughts and ideas continued to flow, but action was elusive. As a citizen artist, I had to act. Remembering news reports of, and experiencing some of the protests of the 60's, I had to be present, to consciously address what I perceived as the slipping away of our humanity.

With my mother's passing, I was acutely aware of the end of a familial era. And with the two and now one remaining of that generation in feeble health, there are so many stories that will go untold. They are stories that feature accounts of ordinary people living ordinary lives and often doing extraordinary things, mostly quietly, sometimes not so quietly, always with firmness and dignity. In general, my family made advances and came to live in relative comfort, but not without struggle.

Being is enough. Living in otherness is a political act. To be other is to have your history altered if not erased, to be routinely maligned (or maimed, or worse) without acknowledgement. To be conscious of these negative forces is a political act. To thrive in spite of them is a political act. To find joy, to create, to contribute to culture, despite lack of attribution, is a political act.

Today's events compel me continue to present accounts of the past, for those accounts serve as witness to how we were, are, and came to be.

Previously, I thought my work to be apolitical. It is quiet, thoughtful, and introspective in meaning and presentation. But quietness can be deceiving. To be other means to be placed at a boundary, sometimes kissing it, but never truly crossing it, and that border colors the lens in which we are viewed (and in some respects, how we view ourselves). Making freely without boundaries is an act of resistance.

My focus is moving slightly from allowing the stories to stand alone to presenting them in juxtaposition to current events while retaining emphasis on identity. I will continue to create for the sake of creating because doing so is in alignment with those who came before me. In both acts, I honor my forebears by continuing to tell their stories and to spend my inheritance thoughtfully, quietly and firmly.

beginning

The room was nice and cozy as about fifteen of us huddled around the table in anticipation. This is when we were going to get to the “meat and potatoes,” where we would unearth a subject for our books. We were told that the writing exercise would help us to formulate ideas for our project. We cleared our spaces of everything except paper, our pens poised in our hands as we readied for the rapid-fire questions that were to come. “Get ready,” we were told, “you’ll only have about one minute to write your answer for each question.” And so the exercise started, each of us furiously wrote our answers – a race to write down all our immediate thoughts and to keep up.

Things went smoothly until this question was posed: “Who are you?” Well, who am I? What – gender, age, profession, ethnicity, belief, family status – is distinctly different from who. What can be easily answered in a minute, but who takes much more time. I was barely able to answer the remaining questions, as “who” kept nagging at me. After the exercise, we looked over our answers, but truthfully, my remaining sentences were a jumbled mess. The only question that really held my interest was “Who am I?”

Now believe me, I realize this is a common question that I’d answered many times before, but somehow, this time it caught me in a way that was downright nagging. It brought me to understand why my work addresses the quest for understanding identity and all it encompasses. For example, I understood a clear connection between my painting and my mother’s sewing, my grandmother’s quilting and crocheting and my great aunt’s tatting. This line extends past my family, linking us to a particular culture and place, and beyond. Each individual, quiet story coalesces to form a cultural memory that is shaped by experience, ritual, belief, places and relationships, and is called upon to explore connections.

Eventually, the book was completed, but my project continues. It continues when stories that reference culture, the body, memory, and place are shared. It continues when an object relays an experience, either by paint, thread or paper. It continues.

Why I like to touch a book

Two things happen when you open a book. If it’s a new book, when you open it the cover gives way with a crackle and then you get the smell of air and ink. The pages are proud and resistant in a new book.

If it’s an old book, the cover surrenders more easily to reveal a bit of history left behind by those who’ve read it before. The pages will smell too, but in the older book the smell is different from that of a new book, like new clothes versus old clothes, even if they’re clean. As you turn the pages, you might hear a slight rustling sound; the pages are softer and more pliable in an older book.

But before you even touch the book, you notice its size. This gives you some indication as to the amount of commitment it will require. As you start reading the book, you can measure time and distance according to the progression of your place within it – where you are, how far you’ve come, and how much more to travel.

Then there’s the feel of the paper. Maybe it’s a book of poems with creamy pages of thick deckled rag, or a tome consisting of thin almost transparent onion skin with a sharpened golden edge. Or it might be an offering of jet black type that plants itself firmly and digs into the page.

Sometimes the physicality of a forgotten book beckons from a shelf - maybe you see just a hint of the spine or cover, or there might simply be a certain quality to its stance - and seeing it makes you want to hold it again and remember.